Global Site

Breadcrumb navigation

IDEO's Tim Brown on Corporation, Design and Innovation

The global design consultancy, IDEO's work with NEC

Tim Brown

Executive Chair at IDEO, the global design consultancy. He has written numerous books and articles including "Change by Design" (Harper Business) and "Design for Action" (Harvard Business Review).

Interview by Noriko Takiguchi, Photo: Akiko Nabeshima

Foreword

Today, digital transformation (DX) is at the center of modern organizational strategies. Approaching design thinking from a human perspective has encouraged innovations and evolved DX.

Design thinking helps people generate ideas in a collaborative way that takes full advantage of everyone's perspectives, breaking mental barriers and changing mindsets. There are many examples of big companies using design thinking successfully, such as GAFA.

IDEO is credited with inventing the term "design thinking" and its practice.

How can you use design thinking in your business?

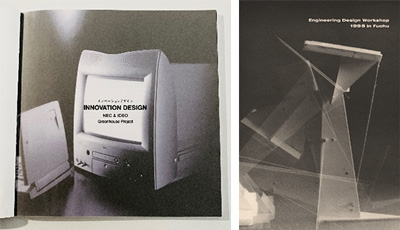

"Engineering Design Workshop"

In the 1990s, NEC and IDEO collaborated on the "Greenhouse Project" and the "Engineering Design Project" for 5 years. We are always thankful for the cooperation of Bill Moggridge who is one of the founders of IDEO. Our "NEC Design Thinking" was influenced by these activities. I have brought various documents and booklets about the former collaboration.

Mrs. Takiguchi, a journalist who knows the projects well, is also here.

Please let us know about activities in the 1990s, the background of design thinking in the 2000s, and the design organization of the next generation.

We'd like to talk with Mr. Tim Brown, Executive Chair of IDEO, who knows a great deal about the growth of Japanese and global companies.

The Greenhouse Project happened at the moment when we all started focusing on human-centered design.

Takiguchi: You participated in NEC's "Greenhouse Project" in which IDEO collaborated with NEC to establish the design language for their products. What do you remember from that experience?

Brown: I started running the San Francisco studio in 1992, and the Greenhouse Project launched in the previous year in 1991. My perspective on the Project was that it was the moment when we all started focusing on human-centered design, and that a part of what we started to express as "design thinking" 10 years later was in those activities -- including user observations, which is going out to meet users and understanding them as the inspiration for ideas. Even though there was some interaction design and a little bit of systems design elements, the Greenhouse Project was about hardware, not services or software. But the underlying concepts of human-centered design were there.

Takiguchi: How did you invent the design language?

Brown: The design language was very much centered around meeting the needs of users. It was all about "Where do people touch products?", "How do they interact with them?" and "What makes products easier to use and easier to understand?". The concept of the design language we developed was very simple and seems very old now, but I think it really was human-centered design. It is part of the heritage NEC designers can refer back to when thinking about service design. Naturally, the services are more complex to design, since they are software, but they start with the same human-centered principle where there are people and processes.

Takiguchi: In the process of developing the design language, I understand the team created simple models called "icons".

Brown: The other thing that was quite innovative about the Greenhouse Project was that the design language was built around a set of principles, not a set of rules. If you think about it, the design language that existed before this, whether it be corporate structure or corporate branding, was always built out of rules and had this big manual. You had to agree with lots of specifications about how everything should be done. And we were very conscious about not wanting to build around rules, so that the corporate designers at NEC would be able to use principles, but still be creative and deal with new situations. We recognized back then that the world was changing faster and faster, and that, if we made a design approach that was based on rules, then those rules would get out of date very quickly. I think those ideas came from Bill Moggridge and Sakakibara-san (Yasushi Sakakibara) who started a conversation a few years before the Project and built this trust. What I loved about Sakakibara-san was his ability to be philosophical and practical at the same time.

Takiguchi: What are the differences between principles and rules in this case?

Brown: Principles are a starting point, and you can go on for infinity. Rules make a boundary, and you can't go outside of it. Now, the difficulty with principles is that they can be interpreted in many different ways, and you can very easily get off track. Thus, it's hard to create visual consistency with principles. So, in the Greenhouse Project, we produced lots of icons between the NEC corporate design team and IDEO to show how these principles could be used. Icons were basically slabs of plastic, which expressed some elements of design, and formed a library of ideas that designers could keep going back to. As we kept doing additional projects, that helped to add to that library.

Takiguchi: What was the status of design activities by other corporate design groups in general?

Brown: Japan, at the time, probably was the strongest anywhere in the world in terms of having corporate design teams and their size. But companies were making hundreds or thousands of products, so the teams were mostly focused on the incremental design works. I think, in a way, when we worked with those teams in partnerships, our contribution was to act as some sort of outside catalyst to help the corporate design teams break out of the day-to-day pressure. It wasn't that the designers didn't know how to do it, but the businesses wouldn't give them permission to do it. Corporations were quite conservative, and it took a lot of effort to get much innovation built into the products. The specs for the products were always determined before the designers got their hands on them, and it made it hard when you want to take a human-centered approach.

Noriko Takiguchi is a freelance journalist based in Silicon Valley, writing technology, business, politics, international relations, and design/architecture for a number of publications. She is a graduate of Sophia University in Tokyo, and was a Fulbright visiting scholar at Stanford University's Computer Science Department.

Design thinking was motivated by designers' desire to work on bigger, more complex problems.

Takiguchi: How was the "design thinking" approach developed?

Brown: We started to use the term in the early 2000s. Actually, it came out of a conversation that David Kelly and I had, where we were trying to figure out how to describe design in a broader sense than just what we did as product designers. David said "Whenever people come and ask me about design, I find myself putting the word 'thinking'." And I said "Oh, there you go." So that's when we started talking about "design thinking". Design thinking is really a helpful term when one wants to democratize design a little bit, to make design accessible to a broader set of people. It is the mindsets and methods that designers are trained how to use, which are very aligned to when we're talking about human-centered design. Some people don't see it this way, but I do. The reason design thinking is relevant to people who are not just practicing designers is that it helps you look at the world through a human-centered lens, so there's a very strong overlap between the two. We talked about human-centered design as being, if you like, the philosophy and design thinking being the practice. The ways we expressed what design is and what human-centered design is -- partly with the Greenhouse Project and also with some other things we were doing -- were the birth of design thinking for us. And of course, it was also the time when people from different disciplines -- like psychologists and computer scientists -- were joining IDEO, and the idea of a multidisciplinary approach to design was gaining some ground. We developed expressions like "user observation" and others which later became the core of design thinking. So, this was a very important time.

Takiguchi: So, you were slowly generating this notion of design thinking as a result of what you were doing in projects. Design thinking approach became widely accepted later.

Brown: I think it was motivated by two different factors. One was the desire to work on bigger, more complex problems. We could see the world was moving from hardware to software, from products to systems, and we believed that, as designers, we needed to be working on those kinds of problems. The other was that we wanted to bring different expertise into the design process. IDEO led with the formation of this idea, I suppose, but we knew we wanted to continue by making design this bigger thing, inviting in other kinds of practitioners, whether they would be entrepreneurs, social scientists or engineers. Again, we needed that in order to be able to tackle these more complex problems.

Takiguchi: Was design thinking also a useful tool when outside designers worked with the client company?

Brown: It was not unimportant to be able to explain to clients what we did, because design is very mysterious to people and many designers keep it that way. In a design-thinking approach, we make it intuitive and brilliant, and clients who have never experienced design before, including people in marketing, finance and engineering, have something to see in the methodologies of design. They can understand why we go out and study users, why you make quick prototypes, and why you visualize ideas in this way, and this makes it a bit easier for those clients to accept that you can help them with their big, important problems. Still, I think there are parts of the design process that are magical and very difficult to explain -- for example, the moments of synthesis when you're taking lots of information. And out of that you pull the idea. That's still very mysterious because it relies on quite a lot of intuition.

One of the new roles for design is to spot opportunities for innovation.

Takiguchi: It's been 20 years since then. How has the design thinking method evolved?

Brown: I think it's evolved in many ways. When we started to explain design thinking, we explained it as a relatively linear methodology, and it clearly never was that. I think now people got much more comfortable with the fact that it's not linear and that you can start in different places. You don't always have to do things in the same order, like you make designs before you do user observations. And we are much more comfortable that this is a more chaotic process. The best design teams are very good at using a chaotic process in whatever the way it meets the needs. Another thing that has changed is the shift to software, and that has changed the way we think about design. In the world of hardware, we designed things and launched them, and then there was this whole process of engineering and manufacturing that was done somewhere else. But in the world of software, you are kind of launching all the time, and you're designing all the time, and designers have to infuse themselves much further downstream as well as upstream. I think the connection between designing and making has got much closer in the world of software than in the world of hardware. It's also made it very important to have people who understand how to build code in design teams. I think yet another piece of the change was the focus on innovation. One of the new roles for design is to spot opportunities to create totally new things, and I think now there is an assumption that design feeds innovation. It doesn't just improve the world but creates new versions of the world. And that means designers need to be entrepreneurial. Without design thinking, I'm not sure that designers would have had the permission to participate in innovation in the way we do now.

Takiguchi: How can design thinking spot new opportunities?

Brown: In my view, designers have new insights as we understand the world in a different way. And we're really good at visualizing the future, which is one of our secret weapons. In that sense, we understand the world differently from the way marketing people understand the world, or the way engineering people and the business people see the world, and thus definitely have different ideas. But we only get the opportunity to work on the innovation if we also take on the responsibility, which means that we have those new ideas in a way that isn't just interesting, or creative, or even just desirable to users. It also has to be technically feasible to make, viable in terms of ultimately creating business value, and desirable so that it will be something that people want. If you're going to get involved in innovation, you have to be able to think about all those things.

Takiguchi: What strengths and potentials do you think corporate design groups have now?

Brown: There has been a rapid and very large-scale transformation of corporate design here in America. When I came to the Bay Area from Britain in the 80s, there were almost no corporate design teams except at Hewlett Packard. And then companies like Apple started to build one. Now, every large tech company in the Bay Area like Google, Facebook and Airbnb has hundreds of designers. But they are not corporate design studios in the traditional sense, rather they almost always spread through the businesses. Apple has a tiny corporate design studio with 25 people, but it's really just for industrial design, and the rest is spread throughout the company.

Takiguchi: What does that mean as an organization?

Brown: That means two things. Firstly, the business values design. Otherwise, they wouldn't have designers in all businesses. And the designers have influence every day. There are also a lot of senior design leaders all over the place. The downside is that they never feel like single communities, so they can easily get overwhelmed by the engineering or business cultures. Still, there's been an enormous investment in design, and nowadays it's gone outside of tech, for instance to healthcare.

Takiguchi: What would be an ideal process in corporate designs?

Brown: Everything is impermanent, and I don't think there's a perfect solution. I do think that, if anything, I would measure the rightness or the fitness based on how adaptable it can be. What we know is that change is constant, and that the volatility of the world is increasing. Therefore, if design is supposed to be one of the activities that allows you to deal with volatility, it should learn quickly and then turn that learning into things that a company can do. Design itself and design organization need to be adaptive. In that sense, we at IDEO are constantly experimenting with different communities -- different ways of connecting together and different ways of working together.

Takiguchi: Thank you for your great input.