Global Site

Breadcrumb navigation

Creating HAYABUSA, the only probe of its kind

Engineers in charge of system management, structural design, the mechanical systems, and assembly

HAYABUSA was the first probe of its kind to visit an asteroid, observe it, collect a sample, and return to Earth. Everything about the probe had to be thought up from scratch when developing and manufacturing it. Also, once the probe was launched into space, there was no way to repair it. To successfully fly to and from an asteroid for the first time in history, it was necessary to create a system that offered unprecedented reliability - the HAYABUSA mission involved complicated and diverse requirements. Many types of equipment had to be loaded onto the probe, and most of this equipment had to be specifically created for HAYABUSA. At the same time, as HAYABUSA had to be loaded on to an M-V rocket for the launch, the probe could not be too big. Although there were limitations on both the dimensions and materials, HAYABUSA had to be loaded almost to capacity with various types of equipment, and the probe itself had to be set up so as to endure troubles and be highly reliable. Plus, only one probe could be built.

If even a single piece of equipment did not work, the entire mission would end in failure. The NEC engineers who designed and manufactured HAYABUSA were faced with demands that conventional wisdom suggested to be practically impossible.

However, the results of their work are clearly demonstrated by HAYABUSA's success. The probe built by these engineers flew through space for seven years - three years longer than the original plan - and successfully delivered the re-entry capsule to Earth.

In the following interview, four individuals look back on the many difficult years they faced: Mr. Oshima, who arranged the overall HAYABUSA system, Mr. Okudaira, who was in charge of structural design responding to Mr. Oshima's demands, Mr. Shouji, who was in charge of the mechanical systems, and Mr. Nishine, who used expert techniques to assemble HAYABUSA.

Toward total optimization

System Manager,

NEC Corporation

- Everyone here had a hand in building HAYABUSA, but what were your individual roles?

Oshima: I was the system manager. We also had a project manager, just like at JAXA. For HAYABUSA, Mr. Hagino, who was introduced in Tale 2, handled this job. The main role of the project manager is to manage the staff, budget, and schedule, as well as to determine the overall direction of the project.

Basically, the project manager is responsible for setting up the overall plan based on an understanding of technical issues so that development can proceed smoothly.

The system manager, on the other hand, is the technical manager responsible for the probe as a whole. You can imagine that some problems will occur when developing a probe. For example, although the total probe weight and power are limited, each on-board piece of equipment has minimum weight and power requirements. It was my job as the system manager to determine which parts to change to improve the overall probe design and how to change parts to ensure probe balance. I also had to provide instructions to engineers.

- So, what you mean is that you look at the probe as a whole, instead of individual pieces of equipment, to distribute resources in a balanced way?

Oshima: That's right. The parts of a probe, which we call components, include various pieces of on-board equipment. The system manager finds a way to connect these pieces of equipment so as to satisfy the requirements of the probe as a whole. There are many constraints, such as on the weight, power, temperature, attitude, sensor field of vision, positional relationships between pieces of equipment and the center of gravity. There are also constraints on the internal plumbing and wiring. Let’s say, some parts cannot exceed certain lengths, and some wiring cannot exceed certain temperatures. My job is to optimize the probe as a whole to satisfy all the constraint requirements.

- So, it's obviously not enough just to fill up the probe with all the individual pieces of equipment?

Oshima: Yeah, just optimizing the individual components does not optimize the probe as a whole. That's why I'm there to oversee the probe as a whole and make sure that the necessary adjustments are made.

Okudaira: And the ones who actually responded to Mr. Oshima's impossible demands for HAYABUSA were Mr. Shouji and I .

Oshima: What, did I really make impossible demands? I sure don't remember anything like that…

Shouji: Yeah, it's a lot easier for the person who makes the demands to forget about them. (Laughs)

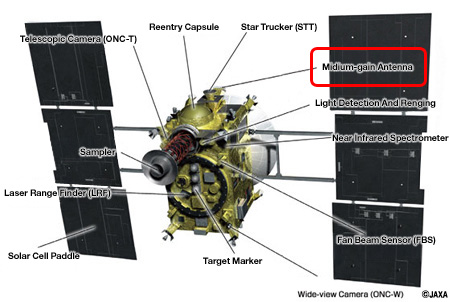

Okudaira: I was in charge of the structural design. Simply put, I guess you could say I determined HAYABUSA's shape. The technical term for this is configuration. My job was to determine how to arrange HAYABUSA’s on-board equipment?including the antennas, ion engines, sampler, and collection capsule?into one probe.

- Was that specific to HAYABUSA?

Structural Designer,

NEC TOSHIBA Space Systems

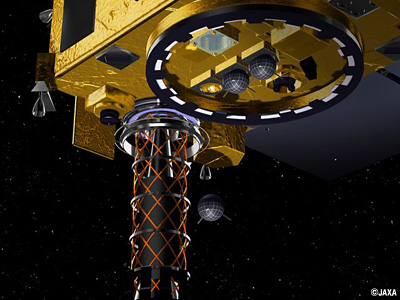

Okudaira: Structural design is required for any satellite, but, because HAYABUSA's mission was to return a sample from an asteroid, the probe had many specialized pieces of equipment and was difficult to design. Take, for example, the sampler, an especially distinctive feature of HAYABUSA. First, since there was no precedent for collecting an asteroid sample, we had to start with sampler research. We had various ideas, including using a sticky substance to collect a sample or wrapping the sample in cloth, but after long discussion, we finally decided to fire a pellet and collect the particles that flew up.

The collected sample also had to be moved to the collection capsule, so we needed to design a transportation route from the sampler to the collection capsule inside HAYABUSA. And, the best place for the sampler was definitely on the bottom surface of the probe at the center, where it passed through the center of gravity. This is because, at this position, the sampler would not cause the probe to lose its balance when it touched down on Itokawa.

HAYABUSA firing a pellet on touchdown (The pellet flew through the inside of the sampler horn.)

Oshima: However, this is still only partial optimization, because the collection capsule had to separate from HAYABUSA when the probe returned to Earth, which means the capsule had to be attached to the outside of the probe. But, if the sampler was attached to the center of the bottom surface and the capsule was attached to the outside of the probe, the transportation route inside the probe would be too long. So, from the standpoint of designing a system that was optimized as a whole, attaching the sampler horn to the center was not acceptable.

Okudaira: To address this issue, after considering many possibilities, we decided to attach the sampler to the edge of the bottom probe surface so as to minimize the length of the transportation route, as close to the collection capsule as possible. Unfortunately, this meant that there was a risk of the probe losing its balance on touchdown. Therefore, we designed the sampler so that it could expand and contract like a car suspension system, absorbing any shock.

Shouji: After the mechanical system engineers, including Mr. Okudaira and me, and the system engineers determined the shape and arrangement of the probe, the next step was to draw up a detailed design. We, the mechanical system engineers, were also responsible for this task. I was in charge of designing the probe and actually drew up the blueprints.

Okudaira: Building HAYABUSA was truly hard work. When the work started, we didn't even know what kind of equipment or how many pieces of equipment had to be installed. And we would have run out of time if we had waited until all this information was collected. We had to do whatever we could with our limited resources.

Teamwork: The key to building a light weight solution

- What was the most difficult aspect of developing HAYABUSA for you?

Okudaira: For me, that would be the temperature environment. Because HAYABUSA had to land on an asteroid exposed to the Sun, we designed it so that the unit can be cooled down easily. And, when the temperature fell, a heater was used to heat up the unit. However, due to launch delays, the target asteroid was changed twice during development.

- The target asteroid was Nereus first, then changed to 1989ML, and finally to Itokawa, right?

Okudaira: That's right. However, when the target asteroid changed, the distance to the Sun on touchdown and the temperature environment changed as well, and so the design had to be revised each time. Of course, this didn't apply just to the temperature environment. Other basic conditions, which have an influence on the design, sometimes changed and became unclear, making revisions very difficult.

Mechanical System Engineer,

NEC Engineering

Shouji: It was definitely tough to change the design when the target asteroid changed. When Itokawa became the target, the orbit changed considerably, so we had to change the oscillation direction of the medium-gain antenna by 90 degrees. However, there was not enough oscillation space on the side on which the antenna had been attached, so the antenna had to be attached in parallel with the direction of travel. Because the internal equipment layout had already been fixed, there was no room to run wiring to the antenna, and, as a last resort, we ran wiring under the high-gain antenna and over the outside of the probe, and then covered the wiring with yellow Kapton insulation material.

- Was doing something like that really okay?

Shouji: It was okay design-wise, but it affected Mr. Nishine’s job of assembling the probe.

Nishine: I'll talk about that in detail a little later. Basically, the effect on probe assembly was large enough to almost make the design impossible.

Okudaira: Not only did the conditions change, but sometimes we didn't even know the conditions required for the design. The design of the sampler horn, for example, depended on where the probe would land. If the probe landed on flat sand, it would have been okay for the sampler horn to be short, but, if the probe landed at a rough, rocky location, the sampler horn had to be tall enough to prevent the solar array paddle and equipment from bumping into rocks. Unfortunately, you would have to actually go to the asteroid to know what the ground is like. Therefore, we ended up having discussions with science professors to determine the probable conditions, but it was hard work. The discussions took a really long time.

Shouji: Regarding the difficulty of developing HAYABUSA, I remember being under extraordinary pressure to reduce the probe weight. If I reported even a tiny increase in the weight at a design meeting, the issue was scrutinized, and resulted in long discussions about where to reduce the weight by an equal amount. Continuously finding ways to reduce the weight posed a formidable challenge to the mechanical system engineers.

Oshima: Regarding HAYABUSA's weight, it was clear from the beginning that, had we performed our calculations based on the maximum conceivable weight, designing the probe would not have been possible. Therefore, our policy was to control the weight by using a standard weight we wanted to keep HAYABUSA under for our calculations, to which we added a margin, but we soon used up the margin and it was extremely difficult to avoid exceeding the maximum weight.

- How did you go about solving all these problems?

Oshima: Whenever there was a problem, I brought it back to the company for discussion. Once we determined the direction we wanted to go in, we went and discussed the problem with JAXA. I really can't stress the importance of considering the total optimization of the project enough. We system engineers attended every meeting about equipment to keep track of the HAYABUSA project as a whole. However, for this probe, total optimization involved more than just the efforts of system engineers. It was clear to everyone that many difficult conditions, including the overall weight constraints, stood in the way of success, and the active cooperation of every engineer in charge of a sub-component was indispensable for creating such a demanding overall design. It's probably the case that, because the difficult problems facing the system were made clear to everyone, the sub-component engineers were able to work in one direction towards overall optimization.

Shouji: I think reducing the weight of the probe structure was one of the most effective ways to reduce the total weight. The structure accounted for a large proportion of the probe weight, so reducing this weight was extremely effective.

When I worked on reducing the weight, I bought and read nonfiction books about the development of the Zero fighter. The Zero fighter was a combat plane whose weight had to be reduced as much as possible. When I got stuck on the design, I just shook my head and reminded myself that my situation wasn't nearly as tough as that faced by the Zero fighter designers.

The end result of my efforts, from the truly tiny weight reductions to the more significant ones, was a close to 20 percent reduction in the original weight of the probe. Not too bad, if I say so myself. (Laughs)

(Handling) Technician,

NEC TOSHIBA Space Systems

Nishine: As I mentioned earlier, once the design was refined, it was left to us to assemble the probe.

Shouji: That's because we trust you guys to do a good job.

Nishine: I guess it's our fate to work together on small satellites under difficult weight conditions. I was in charge of handling, which is incorporating finished parts into the probe. My work included not only assembly but also repeatedly attaching and removing parts each time various tests were performed. For HAYABUSA, a team of several people including me was set up and put in charge of handling.

What HAYABUSA left behind for us

- Was everyone on the team a handling specialist?

Nishine: Yeah, everyone was a pro among pros. That's why not even HAYABUSA caused us too much trouble.

Shouji: I knew you guys would get the job done. We were happy to turn it over to you! (Laughs)

Okudaira: Because HAYABUSA had an extremely complex internal structure, only exceptional engineers could have assembled it.

Shouji: Because we reduced the weight as much as possible, the wiring and other components were barely long enough, and connectors were removed. This made the probe itself as complicated as a puzzle box. Disassembling a certain part, for example, might have involved removing one piece, slipping another in, and lifting still another.

Oshima: Of course, we tried to come up with a design that made overall assembly as easy as possible. We held discussions with everyone involved as we considered the arrangement and configuration of equipment.

Nishine: I said that assembling HAYABUSA didn't cause us too much trouble, but I didn't mean that assembling the probe was easy. It was actually hard. In particular, because many of the harnesses for the probe-internal wiring and connectors for simplifying assembly and disassembly had been removed, assembly and disassembly for testing and other purposes required great care. Plus, HAYABUSA just had a lot of objects sticking out all over the place. These included the sampler horn, antennas, observation sensors, and many others. We had to be careful not to get caught on anything.

Shouji: Not only that, but HAYABUSA had a lot of parts. It had 1.5 times as many as a normal satellite. That's why the inside was totally full and making handling difficult.

Okudaira: There certainly were a lot of parts. We placed the target marker on the inside of the adapter for connecting to the rocket. HAYABUSA is the only probe I can think of where we had to place equipment in places like that.

Bottom surface of HAYABUSA: The target marker and other pieces of equipment can be seen inside the rocket connection adapter (the ring).

Shouji: Yeah, that's because we normally don't place any equipment in places like that.

Nishine: There were even connectors deep inside the probe that only certain people could reach and insert. People who had to check whether they were securely connected had all kinds of trouble. They had to use mirrors to see what was going on.

Shouji: The way you guys moved around the probe during assembly was clearly different from other people. Your movements were always safe. Anyone watching would know that there was no possibility of you guys bumping your heads on the probe. That's why we were sure your team would be able to assemble HAYABUSA as we designed it. We kept the image of your faces in our minds during our work.

Nishine: Unfortunately, veterans like us are becoming scarce. Recently, we have hired young people and started training them, but learning this kind of work requires hands-on experience. It is only possible to learn how to move at an actual job site. Somehow, we need to increase the number of opportunities our young employees have to build satellites.

Shouji: Anyway, building HAYABUSA was hard work. No matter what happened, the launch time couldn't be changed. The HAYABUSA launch time was precisely determined in relation to the orbits of Earth and the target asteroid, and the launch couldn't be delayed.

- But didn't you delay the HAYABUSA launch by changing the target asteroid?

Shouji: Yeah, we did. However, even though we stalled by changing the target asteroid twice, there was no guarantee that such a solution would always be available.

Nishine: At the handling site as well, we started to run out of time as testing proceeded. If there had been no problems, it would have been fine. But, something usually happens that causes a delay. While there was still extra time, we added additional days to the schedule to make up work, but that became impossible, and we eventually ended up unable to go home until the work for a given day was finished.

Okudaira: When the going got tough, Mr. Hagino and Mr. Oshima offered words of encouragement to lift our spirits right when it counted. They were very supportive and encouraging. Their words made me feel like I could do it. As the manufacturer, delays were not an option for us, and there was no choice but to get it done.

Oshima: In contrast, my work was really easy on me. I feel that things proceeded fairly smoothly. However, that's because Mr. Hagino, the project manager, was always working behind the scenes to ensure that things went well. There was never a sense of isolation while developing HAYABUSA. Everyone was involved in everyone else's work. I think such an environment around us led to the good result.

- On June 13th, the day HAYABUSA returned to Earth, what were all of you doing?

Shouji: I watched the return on the Internet at home. I was actually more surprised than happy. After all, this was the first time in history humanity had succeeded in flying to and from an asteroid. I remember thinking that the operation engineers must have faced more difficulties than I could imagine.

Okudaira: At the end of a project, I normally just think, "Well, that's that." However, because I'm involved with the collection capsule, I don't feel like the HAYABUSA project has ended.

Nishine: I anxiously watched the return on TV. I was anxious because I was the one who assembled the mechanism that cut the wiring connecting the collection capsule and probe at the end. I was worried that, since they had been neglected for the seven years since the launch, the moving parts might not work properly, but everything went well.

Oshima: I was at the Sagamihara control room taking part in the final operations. When the communication between the 34 meter antenna at the Uchinoura Space Center and HAYABUSA was lost at the end, Not detected was displayed on the operation display. When I went to the control room the next day, the same message was still displayed. Until the control equipment is turned off, the last displayed screen remains. I wonder who was in charge of that. They probably couldn't bring themselves to turn the power off.

Shouji: Now that it's all over, I think of the work as interesting, but it was difficult while doing it. The JAXA engineers really taught me a lot. My work on HAYABUSA made me a better engineer.

Okudaira: I had tons of experiences with the HAYABUSA probe, and I have been able to apply all of those experiences to the Venus probe Akatsuki. I'm glad I was involved.

Nishine: Both on a personal level and to enable us to train more handling workers, I hope there will be another probe like HAYABUSA soon.

Oshima: If there is ever a HAYABUSA 2, I want to participate and help it succeed. While I accomplished some things with HAYABUSA, there are others that I did not, and I think I could do a better job if I ever have another opportunity.

The HAYABUSA probe was entrusted with an unprecedented mission. Every one of its parts was designed, manufactured, and assembled specifically for that mission.

HAYABUSA is both a machine and one of the world's irreplaceable treasures. The probe represents the culmination of Japanese aerospace development, technology, and ability. On June 13th, 2010, HAYABUSA, which was built by NEC engineers, re-entered the atmosphere and burned up in a glorious ball of radiance. The beautiful result of their efforts exploded into countless tiny particles and dissolved into the atmosphere. However, their experience and confidence remained. They had created HAYABUSA, the first probe to fly to an asteroid and back.

Akatsuki and IKAROS have inherited the HAYABUSA DNA.

Right as HAYABUSA re-entered Earth's atmosphere, Akatsuki successfully fired a new type of engine as it traveled along the orbit leading to Venus. At the same time, IKAROS spread its sail, starting the first solar sail experiment in history. The Age of Discovery for our solar system has begun.

Takeshi Oshima,

Manager,

Space and Satellite Systems Department,

Space Systems Division, NEC Corporation

Joined the company in 1990. Due to his work developing on-board computers, he was the system manager in charge of the technologies of the overall design of MUSES-C (HAYABUSA).

Since July 2003, he has been the system manager in charge of the overall design of the system for PLANET-C (Akatsuki)

Since July 2007, he has been the Akatsuki project manager.

Toshiaki Okudaira,

Manager,

Thermal & Mechanical Systems Group,

Space Engineering Division,

NEC TOSHIBA Space Systems,Ltd.

Joined the company in 1985. He has designed a range of satellite structures and mechanical systems.

He is currently in charge of a scientific satellite mechanical system and structure.

For HAYABUSA, he was in charge of the overall satellite mechanical systems and designing the sampler.

Kazunori Shouji,

Expert Engineer, 3rd Space Systems Development Department,

Mobile Broadband Division, NEC Engineering

Joined the company in 1989. He has designed satellite structures and mechanical systems.

He is currently in charge of a scientific satellite mechanical system and the satellite structure. For HAYABUSA, he was in charge of the satellite mechanical systems and probe design.

Seietsu Nishine,

Group Leader, System Integration Inspection Group,

Manufacturing Headquarters, NEC TOSHIBA Space Systems

Joined the company in 1973. He has worked on manufacturing parts installed on satellites at the Yokohama plant for about 20 years. In 1995, he was put in charge of scientific satellites and worked as the manufacturing leader for Sakigake, Suisei, Akebono, Youkou, Haruka, HAYABUSA, and Akatsuki.

Researched and written by Shinya Matsuura, July 7, 2010