Global Site

Breadcrumb navigation

The miracles brought about by the ion engines

Yasuo Horiuchi, Ion Engine Engineer, NEC Corporation

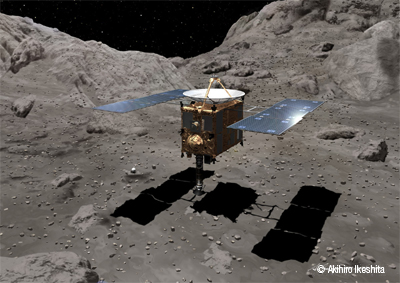

HAYABUSA is a probe that boasts a number of special features. It is equipped with a sampler horn for collecting samples from asteroids, and a re-entry capsule to bring its samples back to Earth. HAYABUSA also has an optical navigation system to enable it to rendezvous accurately with a tiny asteroid in the immense solar system, and various sensors and an autonomous navigation system, to safely descend towards the asteroid.

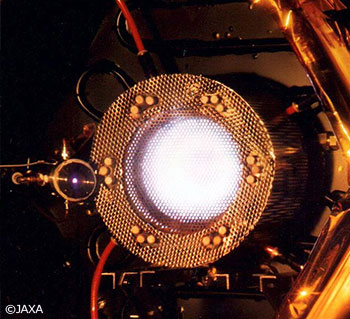

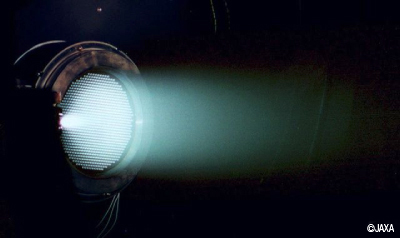

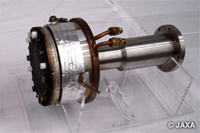

However, the feature that really distinguishes HAYABUSA is its four ion engines. These engines employ a unique system that emits microwaves, like microwave ovens, to ionize xenon, and then the ions are accelerated in an electric field. They are capable of running for a total of 40,000 hours, enabling HAYABUSA to successfully fly to and back from the asteroid Itokawa.

Yasuo Horiuchi has been involved in the development of ion engines since college, and such involvement continued after he joined NEC. For many years, his life has revolved around the ion engines of HAYABUSA.

He calls HAYABUSA a very lucky probe, based on the many miracles brought about by its ion engines.

The impossible is happening

- You have worked on ion engines all along, but what is your background?

Horiuchi: I completed my master's course at graduate school in the laboratory of Professor Kyoichi Kuriki. At around the time research on the type of microwave ion engine used on HAYABUSA began, I participated in prototyping and testing of the first engine. When I joined the laboratory, Professor Kuninaka (Professor of Space Transportation Engineering at the ISAS of JAXA) was in his third year of his doctoral course, and thus he is my senior by four years. For this reason, even now, I personally feel more comfortable calling him Kuninaka-san (Mr. Kuninaka) than Kuninaka-sensei (Professor Kuninaka).

- And this time you are working on ion engines on NEC's side.

Horiuchi: That's right. As I was considering where to work after graduating, I expressed the desire to continue working on ion engines. NEC made me an offer and I decided to work there. Thus, I never had to job hunt.

From around 1993, the HAYABUSA project got underway and I have been continuously working on ion engines since I joined NEC, with the launch in 2003 marking a major milestone.

- HAYABUSA, which carries the ion engines you've devoted yourself to, is now coming back. On the eve of its return, what are your feelings?

Horiuchi: I feel that the impossible is happening. Logically, such a return could only have been described as impossible, but the impossible actually happened a number of times. I believe that HAYABUSA truly is a very lucky probe.

We have done everything we could. A good luck charm from the Temple of Tobifudo (Flying God) hangs in the operations room. The story behind this is that Professor Kuninaka and I agreed that we'd done everything possible, so we decided as our last step to pray to the gods. Professor Kuninaka found a temple with the meaning “to fly” in its name, so I went there to receive a good luck charm. Moreover, I heard that Professor Kawaguchi also went to the Temple of Tobifudo to receive a good luck charm at the beginning of 2006, during the loss of communication with the probe.

- The impossible?

Horiuchi: For example, after the second touchdown on Itokawa in November 2005, the chemical propulsion thrusters, used for attitude control, leaked fuel and became unusable. We had to perform attitude control under these circumstances. We did this by discharging xenon, the propellant for the ion engines, from a neutralizer as a gas. This approach was very far from our minds before we resorted to it.

Normally, under regular operating conditions, the gas that is sent forth from the neutralizer must not generate thrust. Therefore, the generated thrust is only a few micronewtons, and the specific impulse, a measure of rocket performance, is so low that it is supposed to be of no use. However, we succeeded in correcting the probe's attitude. Such an approach would have seemed foolish prior to the launch, and the thought did not occur to us until we were confronted by problems.

- That was truly amazing.

Horiuchi: It happened around the first week of May in 2006, following recovery from the loss of communication. At that time, the attitude of HAYABUSA had been stabilized by spinning the probe. Unless the spin rate was further increased, maintaining attitude stability would become impossible. However, as you know, the chemical propulsion thrusters were no longer operational at that time, and discharging a gas jet from the neutralizer would not only yield poor efficiency but also rapidly deplete the propellant reserves.

At that point, someone suggested using the ion engines. However, I was hesitant to do so because we didn't know what would happen to the injured HAYABUSA if we started the ion engines, which use high voltage. At that time, it took 40 minutes to receive a response from HAYABUSA. If a problem occurred, we wouldn't be able to deal with it immediately. As engineers, we wanted to individually check each piece of equipment and carefully verify its performance before starting operation. But we just didn't have enough time.

Having been involved from development all the way to operations, I was fully aware that HAYABUSA had already been left for dead once, and, figuring we had nothing to lose, gave the command to start the ion engines. The engines started running normally as if nothing had been the matter, and they gave us no trouble at all.

Another instance of the impossible happening was in November 2009, when HAYABUSA's ion engines stopped working. We combined the ion generator of one ion engine with the neutralizer of another to operate as one ion engine. Such cross operation is essentially not testable here on Earth. Suddenly attempting something in space that has not been tested may well cause problems, and any more problems would really have spelled the end. However, we had no other methods left at that time.

At this juncture, Mr. Kuninaka (who seemed like a more experienced engineer rather than a professor) said, “let's do it,” so we implemented cross operation of the engines. And lo and behold, we got propulsive power, and HAYABUSA was able to continue its journey toward Earth.

The operations team passes the baton

- HAYABUSA's ion engines operated for a total of 40,000 hours during the probe's interplanetary space trip. Of course, this is the world's longest use of such engines, right?

Horiuchi: Yes, but at the time of the launch, we were unable to achieve around-the-clock engine operation and it was quite a challenge. We adjusted the operating condition of the engines during the operations period, which was 8 hours a day, and would end that day's operations with the engines kept running as is, only to pick up operations the next day. However, the engines were often stopped with safety systems running. This was repeated day after day.

- Why was this so?

Horiuchi: We assume that rarefied gas remained inside HAYABUSA. During electric discharge, the safety systems would be triggered and the ion engines would stop. It's the same as a circuit breaker being tripped by using too much electricity at home. Of course, we had considered the effect of rarefied gas from the start, but gas discharges from the surface of the probe went on longer than we had expected. If the ion engines stopped along the way, the probe's velocity would gradually become insufficient. The orbit design engineer warned that unless we were able to quickly achieve continuous engine operation, the probe would fail to orbit and would be unable to reach Itokawa. Thus the mission's success depended on the continuous operation of the ion engines.

The first time we succeeded in achieving continuous operation was 6 weeks after the launch. I found myself shaking Professor Kuninaka's hand. Even now, this was the happiest moment I experienced.

The HAYABUSA project is like the Old Maid card game. There are a lot of interrelated factors, and the joker card (the old maid) is always lurking somewhere. If the joker causes trouble on a whim, the probe becomes unable to return. On the way to the rendezvous with Itokawa, it was always the ion engines that held the joker.

In September 2005, when the probe reached Itokawa, I went to the Tokyu Hands department store and bought a large joker card. I wrote “First leg of the journey complete” on that card and passed it on to the touchdown engineer.

On the return leg of the journey, the joker returned to us, the ion engine team. It's been a long stretch, but now it's almost over. The joker will finally be passed on to the team in charge of the re-entry capsule.

At the party celebrating the first anniversary of the launch, I remember saying to Professor Kawaguchi, “HAYABUSA is a lucky probe.” Today, after everything HAYABUSA went through, I can't find a more fitting description. HAYABUSA is an extremely lucky probe.

- You are now in charge of the commercialization of ion engines.

Horiuchi: One application is orbital control of GEO (Geosynchronous Earth Orbit) stationary satellites. GEO stationary satellites, if left to themselves, go off orbit and zigzag northward and southward little by little. A thruster is needed to continuously adjust their orbit so that they remain in a geostationary orbit. This is called north-south attitude control, and the use of ion engines for this purpose reduces the required propellant, allowing longer use of the satellite.

There have been cases of using ion engines for north-south attitude control of commercial satellites by Europe and the U.S., but the reliability of these ion engines has been fairly low and these engines have tended to cause problems.

Therefore, almost no ion engines remain in use today. This is the market that we plan to enter by offering microwave discharge type ion engines, with high reliability developed through HAYABUSA as our selling point.

Following the launch of HAYABUSA, Horiuchi thought that he would like to do something different from ion engine development and requested to be transferred. He was assigned to a section in charge of commercializing new technologies. However, ion engines followed him there too. The reliability required for interplanetary space travel is a force that will continue to create new markets.

Dealing with ion engines for over 20 years since college, Horiuchi had one secret since before the launch. “Actually, I have given my own names to engines A to D on HAYABUSA. I named engine A after myself, engine B after my wife, and engines C and D after my children. And so, when engine A had problems immediately after the launch, “Dad” turned out to be no good… But in the end, we managed to get HAYABUSA to travel back through the cross operation of engines A and B, which I think is a nice conclusion.”

And thus the story of the people supporting the HAYABUSA Team also illuminates the final stage of the journey of HAYABUSA, made possible by the neutralizer of engine A supporting engine B.

Researched and written by Shinya Matsuura (released July 30 , 2010)

Yasuo Horiuchi,

Senior Manager of Satellite Business Development Office, NEC Corporation

Joined the company in 1990. Has been working on the development of ion engines every since, and joined the Satellite Business Development Strategy Office in 2009. He is currently promoting the small satellite business.