Global Site

Breadcrumb navigation

Connecting Space and Earth

Kenichi Shirakawa, Orbit and Attitude Control Manager, NEC Aerospace Systems27 March 2010, 3:17 pm

Radio waves from HAYABUSA arrived from a point in space 27 million kilometers away.

The waves were received using a parabolic antenna for deep space communication that had a diameter of 64 meters and was located in Usuda-machi, at the foot of the Yatsugatake mountains.

The reception signal was relayed via a terrestrial channel to the satellite operations room at the Sagamihara campus of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), located in Sagamihara City, Kanagawa Prefecture. The signal was processed by computer and shown on displays.

The operations room was abuzz with voices.

"Is the orbit system OK?"

"The ion engines are fine. Δv (Delta-v: orbit control variable) is as planned."

"Okay, stop the ion engines! Second stage orbit control has been completed!"

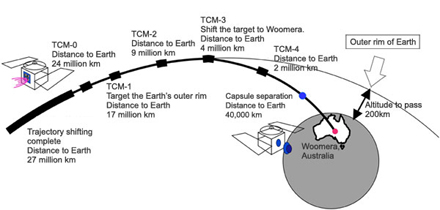

While scrutinizing screens displaying continuously changing data, Kenichi Shirakawa, in charge of attitude control, thought to himself, "Still a little ways to go, can't quite relax yet." Although HAYABUSA had indeed successfully gone on an earthbound orbit, the re-entry capsule could not just fall anywhere on Earth. The capsule was to fall in the Woomera Desert in the center of Australia. This would require several fine orbit adjustments.

HAYABUSA was equipped with a chemical propulsion thruster for orbit correction, but it was rendered useless as a result of the touchdowns on the Itokawa asteroid. The only way left to adjust the orbit was to use the ion engines, which had not been designed for this purpose. There were still a few things to do, which required even more precision than before.

Shirakawa's job was not over yet.

Preparing for HAYABUSA's Return to Earth

- First, how to do you feel about orbit control for re-entry, now that things have settled down somewhat?

Shirakawa: The media report have been reporting that HAYABUSA's orbit control has been completed and that it will be able to return to Earth without incident, but we are still making fine adjustments. As it is these fine adjustments that will allow HAYABUSA to safely return to Earth, we need to be more careful than ever. Having reached this point, there is no turning back.

Two out of the three reaction wheels used to control attitude have failed, and the chemical propulsion thruster normally used for attitude control is no longer operational. So a high level of skill will be required to correctly control the orbit of the satellite while stabilizing its attitude.

- How many more times will you control the orbit?

Shirakawa: We turn on and then stop the ion engine propulsion, carefully measure the orbit, and determine the amount of correction to be applied at the next propulsion. So I can't tell you the exact number. It all depends on the propulsion.

(source: JAXA; with some additions)

- When did your involvement with HAYABUSA start? And what is your main job for HAYABUSA?

Shirakawa: Soon after I joined NEC in 1988, I was put in charge of the Hiten probe, which performed a moon swing-by. Thanks to this probe, I was able to get hands-on experience with various orbit control maneuvers, including swing-by, lunar orbiting, and moon crashing, which really boosted my confidence. After that, I got involved with the LUNAR-A probe, which was discontinued, and then HAYABUSA. During the development stage, the probe didn't have a nickname and was just referred to as MUSES-C.

During the development of HAYABUSA, I was mainly in charge of the attitude and orbit control software for the onboard computers. This being my first experience operating an ion engine, which runs on electric power, and performing touchdown on an asteroid, it was quite a challenge.

My work has not been limited to development, and I've been involved for quite some time now with the actual operation of HAYABUSA after the launch.

- It's been seven years since the project was started in May 2003. Have your feelings about your involvement with HAYABUSA changed since then?

Shirakawa: I don't really get the impression that I've been on it a long time. From the launch in 2003 until the approach of Itokawa in 2005, I feel that I've just been fulfilling my role of taking care of the subsystems I took charge of. I guess things changed from the touchdown on Itokawa in the fall of 2005.

- What happened, and how did things change?

Shirakawa: So many unexpected things happened that we no longer could claim such-and-such as our scope of responsibility, and the whole team had to look over all aspects concerning HAYABUSA…

For a long time following the launch of re-entry operations in 2007, the distance between the Earth and HAYABUSA was great, and when HAYABUSA was particular distant, information would trickle in at the rate of 8 bps (the equivalent of 1 character) per second. Obtaining the required amount of information would take hours, this kind of operation. What's more, it would take as much as 40 minutes for the waves to travel back and forth.

At that time, I felt like a watchman looking over a slowly burning bonfire.

- A watchman?

Shirakawa: Yes, a watchman. I feel like I've been holding a really, really extended dialog with HAYABUSA covering all kinds of things. And so, looking over the last 7 years, I don't feel like it's been a long time.

Clearing various hurdles

- What has struck you the most in your operations work?

Shirakawa: I suppose it was the two touchdowns we did in November 2005. For one thing, we had a series of unforeseen events. For starters, Itokawa had an unexpected surface shape, and a number of anomalies had developed in the probe by then. Fully autonomous operation had become difficult.

In the process, what I think worked best when we hit unexpected obstacles was to carry on operations with human intervention, making judgments at pivotal points. At that time, the operations teams of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and NEC would come up with new operation methods on a daily basis. This made us realize the power of human beings, who can achieve things machines can't.

That's right, following the touchdown in November 2005, there was a period during which HAYABUSA became unable to determine its attitude, it lost its power, and we didn't know where it was. When we again captured the beacon wave toward the end of January 2006, we were truly surprised.

Thinking that it would take a while longer until we caught it again, and assuming that I wouldn't be back in the operations room for a while, I had gone back to tidy things up, and that's the very day it happened. Somebody cried out, "Looks like HAYABUSA's beacon!"

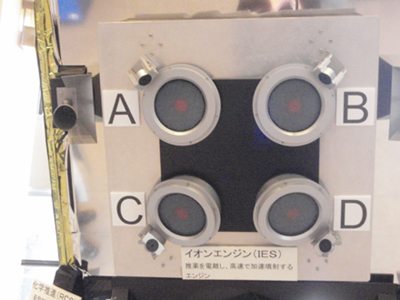

- What went through your mind when the ion engines developed anomalies in November 2009? What was your reaction when you had to use two ion engines, A and B, out of the four, to perform the work of one engine, and the probe actually moved?

Picture of full-scale model of HAYABUSA in the ISAS lobby

Since November 2009, neutralizer A and ion beam B have been

used in combination to operate as one engine.

Shirakawa: At that time, I felt like taking my hat off to the ion engine designers, who provided a bypass circuit to the power supply system to cover just such a situation. At that instant, I thought, "This has saved us. HAYABUSA is like a cat with nine lives." Really, this probe, though weighing in at just a little over 500 kg, is tough and has luck on its side.

- The operation will be over soon, but what will you be concentrating on the most during the time that is left?

Shirakawa: Definitely, ensuring an accurate orbit and guiding HAYABUSA safely to Earth.

- What do you think you will feel once the capsule comes back?

Shirakawa: Once the capsule comes back? "HAYABUSA, thanks for the hard work," I suppose. That's rather trite though (laughs).

- Having accomplished this 7 year long mission, what do you want to do next?

Shirakawa: I haven't thought about it, but my answer will have to be work on HAYABUSA's successor. I'd like to relay to young people the lessons I've learned over these 7 years and the various software and tools we've developed. But this being the kind of stuff that is difficult to transmit in writing, I would like to create opportunities to relay this knowledge through actual operations.

A full-scale model of HAYABUSA is displayed in the ISAS lobby at the Sagamihara campus of JAXA. Now and then, coworkers catch sight of Shirakawa standing at its side, gazing at it at length.

In his own words, "Looking at this model, I confirm my image of how the actual HAYABUSA works when changing its attitude, etc."

As of the end of March 2010, looking up at the sky from Japan, one could see HAYABUSA rise over the eastern horizon at 3 pm, and sink toward the western horizon in the middle of the night, heading straight toward the Earth. This time frame coincides with Shirakawa's working hours.

Shirakawa's dialog with HAYABUSA will continue until the re-entry capsule separates from the body of the probe a few hours before re-entry.

Until then, he will serve as the go-between for a probe out there in space and Earth.

Based on an interview on March 29, 2010

Kenichi Shirakawa,

Expert engineer of 3rd Engineering Department, Space Systems and Public Information Systems Division, NEC Aerospace Systems

In charge of attitude and orbit control systems of deep space probes (HAYABUSA, Kaguya, etc.). Has been involved continuously with HAYABUSA from the development phase to current operations.